Problem Statement:

Genetic conditions frequently present with pronounced and distinct facial characteristics, which are often the first clue in clinical diagnostics. To this day, a clinical diagnosis relies on an assessment by the clinical experts who are trained to recognize either facial features or a ‘gestalt’ associated with the syndrome. Recently, however, objective phenotyping approaches for assessing the face have proven to be successful in providing automated assistance for clinical diagnosis [1–3]. Previous work on syndrome identification has mostly focused on 2D facial images. While 2D photographs are easier to obtain, 3D images capture facial shape completely and more directly and are not subject to projection distortion, which is inherent to all 2D imaging modalities. Given the increasing accessibility of 3D imaging hardware, including smartphones, studying the potential of 3D shape analysis for syndrome classification is very promising. Previous work in this domain has used linear dimensionality reduction and classification techniques and has typically focused on discriminating one or a few syndrome groups from controls [4,5]. The most comprehensive attempt at multi- syndrome classification deployed these linear techniques on 64 syndrome groups, with classification based on a sparse configuration of 65 anatomical facial landmarks [3].

Deep convolutional neural networks (DCNNs) have recently been deployed for syndrome identification based on 2D images [1, 2]. To learn from 3D data, some approaches transform the data into the Euclidean domain using a 2D UV- or 3D voxel-representation [6,7] or learn from the point cloud using geometric deep learning (GDL) [8]. However, 3D to 2D transformations, voxelization, or ignoring the local connectivity of the mesh by reducing it to a point cloud may cause significant loss of information of the underlying geometry. With recently introduced GDL techniques [9], it is now possible to apply deep learning directly on the non-Euclidean facial surfaces, which are discretized as graphs or

meshes [10–13]. Drawing from this literature, we use spiral convolutional operators which apply local anisotropic filters to features given on a non-Euclidean domain, mimicking the classical convolutional filters used in CNNs [10, 14–16]. These operators are applicable to meshes that share a common topology, as for the 3D facial data in this work. While classification loss functions such as cross-entropy are commonly used for classification tasks, we use deep metric learning instead to learn the distinguishing facial features based on similarity measures. More specifically, we implement a triplet-based architecture and train it with a triplet loss function [18]. The advantage of the triplet loss is that it can efficiently learn a large number of classes, even with a small number of samples per class [19,20].

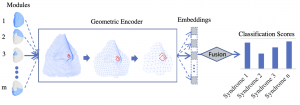

Since the human face comprises multiple integrated parts that are distinct from each other based on their anatomy, embryological origin, and function, facial dysmorphism can be described by defining atypicalities in each part of the face. In the literature, part-based approaches have been employed, mostly for 2D images, in which separate models are trained for local regions such as the eyes, nose, mouth, and chin, along with the entire face [1, 21]. Inspired by this idea, in this paper, a part-based Geometric Encoder (GE) is proposed to reduce the dimensionality of the variation among 3D meshes. This is executed by learning a supervised lower-dimensional embedding space or metric space by GDL, for the first time, for multiclass syndrome classification. Figure 1 shows the general pipeline. Initially, a low dimensional embedding vector is learned for each facial module using a separate GE block. We experiment with various fusion techniques to combine embeddings or classification scores across multiple facial modules, in order to form a more reliable classification model. Performance of the geometric encoder is benchmarked against principal component analysis (PCA), which is the commonly used unsupervised linear dimensionality reduction technique in 3D facial shape analysis. For each embedding type (PCA and GDL), we assess the contribution of the part-based setup by comparing its performance to using the full face.

Facial Segmentation and Part-Based Learning:

A data-driven hierarchical 3D facial surface segmentation using spectral clustering was presented in [27]. The segmentation sequentially splits the vertices of the facial surface into smaller subsets called modules, such that covariation within modules is maximized and covariation between modules is minimized. Here, we simply adopted the first four levels of this modular segmentation as shown in Figure 2. The mesh-padding techniques used for implementing part-based encoders in shown in Figure 3.

For further elaboration on the network design please refer to the materials and methods section of the paper.

Results & Discussion

In today’s era of image-based deep learning, CNNs have only been deployed on 2D images in the context of syndrome classification [1,2]. This is the first study to apply geometric deep learning to multi-class syndrome classification. We derived full-face and propose part-based geometric encoders to encode observations into non-linear metric spaces, supervised to separate among classes. These embeddings were then subjected to classification by LDA. We experimented with the dimensionality of the space and different methods of fusion for the part-based encoders. We compare the results to those using linear embedding spaces derived from PCA.

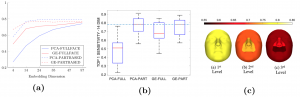

Figure 4a shows the mean sensitivity of the full-face and the best part-based models for both PCA and GE. It indicates that, for the full-face method, GE significantly outperforms PCA, although this discrepancy becomes smaller as the number of dimensions increases. This is mainly because GEs are trained in a supervised way (in contrast to PCA) therefore the embeddings are trained to preserve the most relevant information to the discrimination task. This is likely to include localized facial features only common to a small proportion of the training set (e.g. to one particular syndrome). PCA ultimately learns these too but it takes additional dimensions to do so, because it only aims to preserve the maximum amount of variation across the entire training dataset. Therefore, its first dimensions will capture broad patterns of facial variation and population structure and not specific discriminative facial features. Figure 6 of supplementary material depicts a 2D visualization of the 14 dimensional part-based PCA and GE projections of the train set (smaller dots) and test set (larger dots) using t-SNE [29]. This plot clearly demonstrates that the GE learns a better structured metric space in which distinct syndromes reside into clusters.

According to Figure 4a, the part-based approach boosts the performances for both GE and PCA. The improvement is the largest for PCA, especially with lower dimensionality. Using the part-based scheme, localized information of the face is forcefully injected into the model using the modular encoders. For PCA, this means that, even with low dimensionality, localized shape variation remains available, which is otherwise lost in the context of the full face only. For the PCA model, adding modules to the analysis has a similar effect to increasing the dimensions of the full-face model. According to Figures 4a and 4b, the gain in using the part-based approach is still notable for GE. Using a part-based scheme at 14 dimensions per module, performance approaches the ceiling, suggesting that the discriminative facial variation is represented compactly by both approaches when using a part-based scheme.

Using a part-based approach requires a fusion of information across multiple facial modules. We examined both feature- and score-level fusions, with the former yielding better performance. The superiority of feature-level fusion signifies the importance of combining feature information from all parts of the face to build an accurate classifier. The superiority of the part-based approach further demonstrates that information from each part of the face is best learned first in a part-based manner and then combined. For more information, the average sensitivity over 5 folds for all experiments, and the confusion matrix of the best part-based GE model are reported in Table 2 and Figure 5 in the supplementary material.

Aside from strengthening the prediction model, another advantage of part-based classification is gaining the opportunity to quantitatively and qualitatively measure the contribution of each facial module in the final classification of each syndrome. The latter is highly interesting since it allows us to compare the facial modules that contribute to the automated classification with the clinical features that are used by expert clinicians to recognize a particular syndrome. E.g., in Figure 4c, we visualize the significance of each module in classifying 22q11 2 deletion syndrome for the first three levels of the hierarchical segmentation. The color of each module is indexed to the top 1 sensitivity computed from individuals with 22q11 2 deletion syndrome. While there is wide inter-individual variability in the presence of mild dysmorphic features in 22q11 deletion syndrome, the most consistent feature is a tubular nose with underdeveloped alae nasi and a round nasal tip. Consistent with this, the sensitivity map in Fig. 4c (b) and (c) indicates the contribution of the nasal module in the automated classification.

In this work, we proposed a 3D part-based GDL model as an assisting tool for identifying candidate disorders based on facial shape. Obtaining a 2D photorealistic equivalent from our 3D dataset is not straightforward. However, once available, it is of interest to compare the results of this study with the 2D CNN implementations commercially available, such as FDNA. Lastly, studying the properties of the metric space learned by our geometric encoder and investigating the extent to which they reflect the functional relationship among the genes are among the future perspectives of this work.

References

- Y. Gurovich et al., ”Identifying facial phenotypes of genetic disorders using deep learning,” Nat. Med., vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 60–64, Jan. 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41591-018-0279-0.

- Q. Ferry et al., ”Diagnostically relevant facial gestalt information from ordinary photos,” eLife, vol. 3, p. e02020, Jun. 2014, https://doi.org/ 10.7554/eLife.02020.

- B. Hallgr ́ımsson et al., ”Automated syndrome diagnosis by three-dimensional facial imaging,” Genet. Med., Jun. 2020, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41436-020-0845-y.

- S. Fang et al., ”Automated diagnosis of fetal alcohol syndrome using 3D facial image analysis,” Orthod. Craniofac. Res., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 162–171, Aug. 2008, https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1601-6343.2008.00425.x.

- P. Hammond et al., ”Discriminating Power of Localized Three-Dimensional Facial Morphology,” Am. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 77, no. 6, pp. 999–1010, Dec. 2005, https://doi.org/ 10.1086/498396.

- Zhirong Wu et al., ”3D ShapeNets: A deep representation for volumetric shapes,” in 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recogni- tion (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, Jun. 2015, pp. 1912–1920, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298801.

- D. Maturana and S. Scherer, ”VoxNet: A 3D Convolutional Neural Network for real-time object recognition,” in 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on In- telligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, Sep. 2015, pp. 922–928, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/IROS.2015.7353481.

- R. Q. Charles, H. Su, M. Kaichun, and L. J. Guibas, ”PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation,” in 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, Jul. 2017, pp. 77–85, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR.2017.16.

- M.M.Bronstein,J.Bruna,Y.LeCun,A.Szlam,andP.Vandergheynst,”Geometric Deep Learning: Going beyond Euclidean data,” IEEE Signal Process. Mag., vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 18–42, Jul. 2017, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/MSP.2017.2693418.

- I. Lim, A. Dielen, M. Campen, and L. Kobbelt, ”A Simple Approach to Intrinsic Correspondence Learning on Unstructured 3D Meshes,” ArXiv180906664 Cs, Sep. 2018, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2020.. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1809.06664.

- J. Bruna, W. Zaremba, A. Szlam, and Y. LeCun, ”Spectral Networks and Locally Connected Networks on Graphs,” ICLR, 2014.

- M. Defferrard, X. Bresson, and P. Vandergheynst, ”Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering,” in Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, Dec. 2016, pp. 3844–3852, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2020. .

- F. Monti, D. Boscaini, J. Masci, E. Rodola`, J. Svoboda, and M. M. Bron- stein, ”Geometric deep learning on graphs and manifolds using mixture model CNNs,” ArXiv161108402 Cs, Dec. 2016, Accessed: Jun. 20, 2020. . Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1611.08402.

- G. Bouritsas, S. Bokhnyak, S. Ploumpis, S. Zafeiriou, and M. Bronstein, ”Neural 3D Morphable Models: Spiral Convolutional Networks for 3D Shape Represen- tation Learning and Generation,” in 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Korea (South), Oct. 2019, pp. 7212–7221, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/ICCV.2019.00731.

- S. Gong, L. Chen, M. Bronstein, and S. Zafeiriou, ”SpiralNet++: A Fast and Highly Efficient Mesh Convolution Operator,” in 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshop (ICCVW), Oct. 2019, pp. 4141–4148, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/ICCVW.2019.00509.

- D. Kulon, R. A. Guler, I. Kokkinos, M. M. Bronstein, and S. Zafeiriou, ”Weakly-Supervised Mesh-Convolutional Hand Reconstruction in the Wild,” in 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recogni- tion (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, Jun. 2020, pp. 4989–4999, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00504.

- F. Schroff, D. Kalenichenko, and J. Philbin, ”FaceNet: A Unified Embedding for Face Recognition and Clustering,” 2015 IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recog- nit. CVPR, pp. 815–823, Jun. 2015, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298682.

- E. Hoffer and N. Ailon, ”Deep Metric Learning Using Triplet Network,” in Similarity-Based Pattern Recognition, vol. 9370, A. Feragen, M. Pelillo, and M. Loog, Eds. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015, pp. 84–92.

- A. Hermans, L. Beyer, and B. Leibe, ”In Defense of the Triplet Loss for Person Re-Identification,” ArXiv170307737 Cs, Nov. 2017, Accessed: Mar. 01, 2020. []. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1703.07737.

- J. Lee, N. J. Bryan, J. Salamon, Z. Jin, and J. Nam, ”Metric Learning vs Classification for Disentangled Music Representation Learning,” ArXiv200803729 Cs Eess, Aug. 2020, Accessed: Nov. 09, 2020. []. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/ 2008.03729.

- O. Ocegueda, S. K. Shah, and I. A. Kakadiaris, ”Which parts of the face give out your identity?,” in CVPR 2011, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, Jun. 2011, pp. 641–648, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR.2011.5995613.

- O. Klein, W. Mio, R. Spritz, and B. Hallgrimsson, ”Developing 3D Craniofacial Morphometry Data and Tools to Transform Dysmorphology.” FaceBase (www.facebase.org), 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.25550/TJ0.

- J.D.Whiteetal.,”MeshMonk:Open-sourcelarge-scaleintensive3Dphenotyping,” Sci. Rep., vol. 9, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Apr. 2019, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-019- 42533-y.

- O. Ekrami, P. Claes, J. D. White, A. A. Zaidi, M. D. Shriver, and S. Van Dongen, ”Measuring asymmetry from high-density 3D surface scans: An application to human faces,” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 12, p. e0207895, Dec. 2018, https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0207895.

- S. S. Mahdi et al., ”3D Facial Matching by Spiral Convolutional Metric Learn- ing and a Biometric Fusion-Net of Demographic Properties,” ArXiv200904746 Cs Eess, Sep. 2020, Accessed: Oct. 16, 2020. . Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/ 2009.04746.

- J. Hu, J. Lu, and Y.-P. Tan, ”Discriminative Deep Metric Learning for Face Verification in the Wild,” in 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Jun. 2014, pp. 1875–1882, https://doi.org/ 10.1109/CVPR.2014.242.

- P. Claes et al., ”Genome-wide mapping of global-to-local genetic effects on human facial shape,” Nat. Genet., vol. 50, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Mar. 2018, https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41588-018-0057-4.

- T. Hastie and R. Tibshirani, ”Discriminant Analysis by Gaussian Mixtures,” J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol., vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 155–176, 1996.

- Maaten, L.v.d., Hinton, G.: Visualizing Data using t-SNE. Journal of Machine LearningResearch9(86), 2579–2605 (2008), http://jmlr.org/papers/v9/ vandermaaten08a.html