Recent advances in deep learning and computer vision have made a significant impact on a variety of domains. However, there is a fundamental and often overlooked shortcoming of these techniques when applied to biological and medical image data. Hence, it is of interest to examine the biological plausibility and interpretability of the knowledge learned by deep networks. Particularly within this study, we aim to use 3D images to investigate the existence of multiple patterns of sexual dimorphism in human faces. The outcomes of this study can potentially result in a powerful alternative to the current linear biological shape analysis which provides only a single metric for sexual dimorphism.

Data

Studying facial morphology requires a 3D-face representation that can reflect the shape variations in high detail. The datasets used for this thesis consist of spatially dense networks of quasi-landmarks. These 3D meshes are constructed according to the following steps:

First, the 3D images were captured using 3DMD and Vectra H1 3D imaging systems. Subjects were asked to have a neutral look and their mouth closed. Images are further purified by removing hair and ears. After scanning and purifying faces, an anthropometric mask, which is a facial surface template, is non-rigidly applied to the faces. The result is a spatially dense network of around 7150 quasi landmarks in which each landmark indicates one anatomical location across all the faces. Then, a Procrustes superimposition is performed to eliminate differences in scale, rotation and position between the quasi-landmarks configurations [1].

Approach

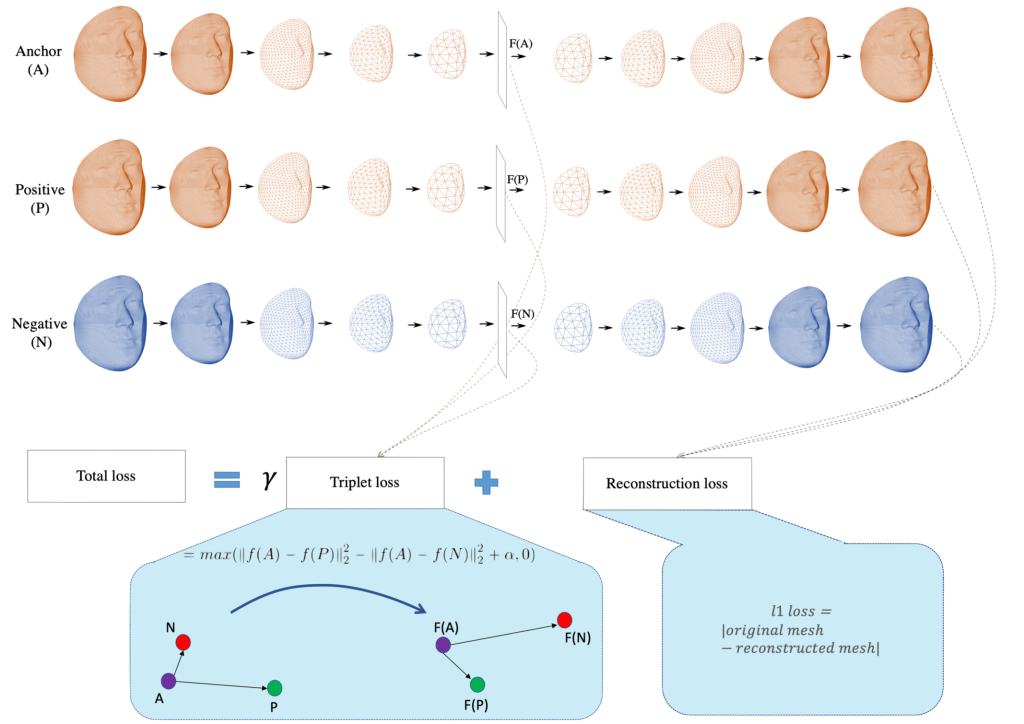

We first train an autoencoder for 3D facial images with a 32 dimensional latent space. Once obtained, the trained model will be fine-tuned for sex classification with the deep metric learner function called Triplet Loss (TL). The overall scheme is shown below:

The advantages of this combination are: (1) Triplet loss is trained with triplets of faces, thus, the number of training data can practically increase to n3. (2) Due to the metric measures included in the TL function, the latent space will reflect the similarity in sex groups, hence distances are meaningful measures for classification purposes. (3) The potentially multiple patterns of sexual dimorphism learned by the network can be visualized with the help of the decoder, which improves the interpretability of the learned model.

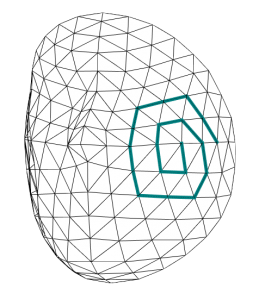

Because we are working with 3D Meshes, we use Convolutional Mesh Autoencoder based on Spiral Convolutional Operator [2]. The idea is to chose a spatial approach based on spiral convolutions.

A spiral is defined around each vertex of the mesh, according to a reference point on the mesh in a clockwise manner. These spirals scan over the mesh as a filter would over an image in regular convolutions.

Results

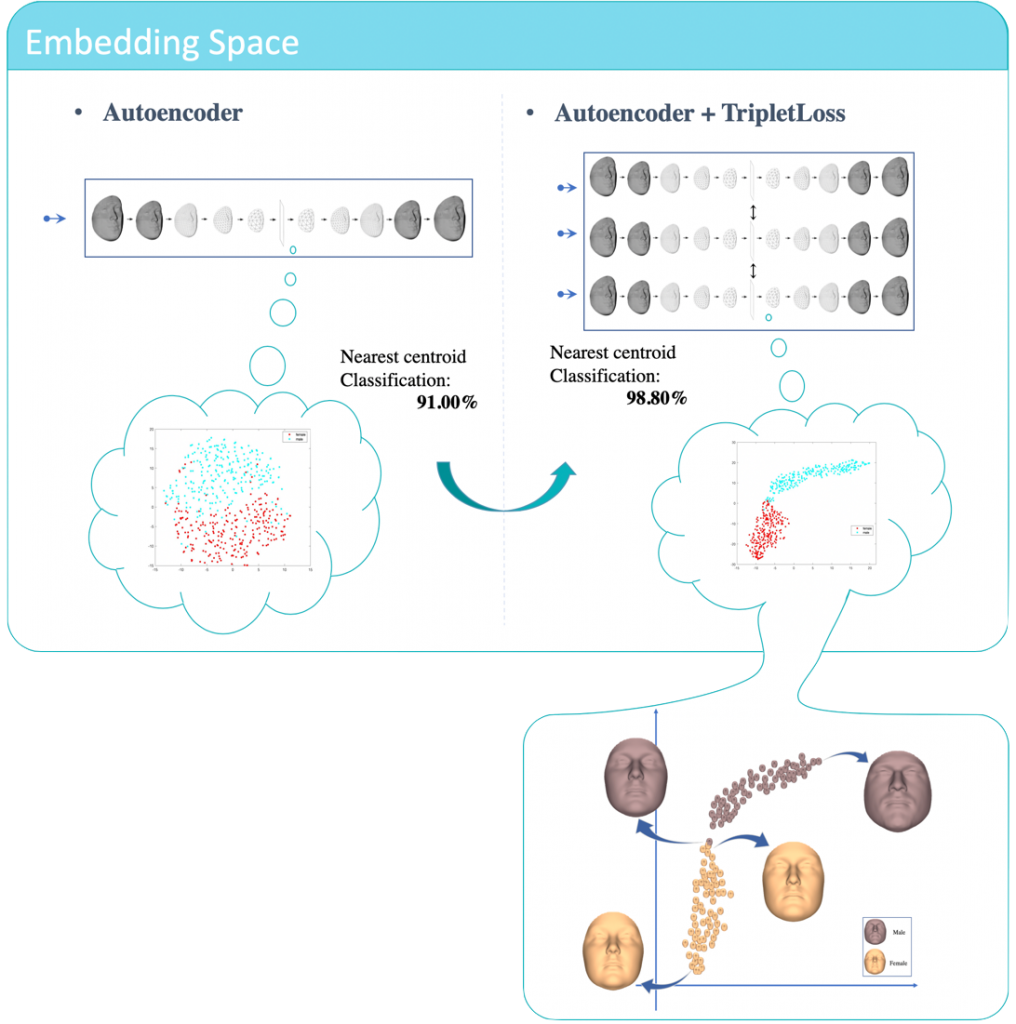

Embedding Space

The Figure below shows the effect of Triplet loss on structuring the latent space. If we look deeper into the latent space, we can extract highest masculine and feminine faces while walking through the latent space. In addition, faces close to the borders show us highly masculine feminine face and vice versa.

Patterns of Sexual Dimorphism

Patterns of Sexual Dimorphism

In order to interpret the meaning of dimensions and distances in latent space, one can tweak the values in embedding space and visualize the effect with the help of decoder.

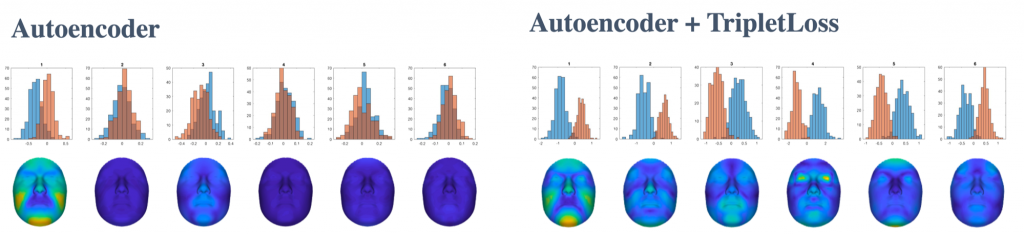

In order to extract sexual dimorphism patterns learned by each dimension, I replace each embedding dimension of an average face, with the corresponding value of male and female average embeddings. then I decode the resulting embedding vectors and subtract them to see the areas in which the differences are the most. Figure below shows the activated regions for 6 highly activated dimensions, both for AE and AE+TL networks.

The comparison of the two results above tells us there can potentially be multiple patterns of sexual dimorphism which linear and even non-linear unsupervised methods cannot easily extract. However, this claim needs further investigation of the correlation between dimensions. The interesting questions that rise from this study can be listed as:

- How correlated are the patterns learned by each dimension?

- What is the improvement when moving from linear to non-linear spaces?

- Will these patterns differ if the model is trained on another population, e.g. Africans or Asians?

- What is the effect of different triplet mining strategies? (hard/easy/random triplet mining)

- How can we deal with uncertain labels in biomedical domain?

- How will deep networks perform in control-disease classification problems where there is no to little difference in facial morphologies. An example of this is ASD in which reported facial phenotypes are very subtle.

References:

- P. Claes, M. Walters, and J. Clement. Improved facial outcome assessment using a 3d anthropometric mask. 41:324–30, 11 2011.

- Bouritsas, G., Bokhnyak, S., Ploumpis, S., Bronstein, M. & Zafeiriou, S. (2019). Neural 3D Morphable Models: Spiral Convolutional Networks for 3D Shape Representation Learning and Generation. ICVSS 2019.

Funding:

- Risk assessment of autism spectrum disorders in infants, 2017-2021, FWO-SBO, Flanders, SBO S001517N

- Vandermeulen, P. Claes and M. Bronstein, Learning Faces from DNA, 2018-2021 FWO, Flanders, research project with SNF, Switzerland, G078518N